Forum:Revisiting fiction with branching elements and historical policy therein/OP

The Damn Introduction[[edit source]]

- "Here we are again, engaged in the Founding Conflict. There is no greater battle than this: the battle between Tardis Wiki and video games."

This was the opening sentence recently given in the closing statement of our forum debate about the game Legacy. While clearly delivered as a bit of a fun joke, I feel it accurately represents one of the most contentious issues on this website. Tardis Wiki is afraid of video games.

The medium is a little stranger than most. Video games associated with the franchise have typically appeared and vanished overnight. Video games are second only to stage plays when it comes to Doctor Who universe experiences which we sometimes can only approximate in current times, making our historical displeasure to their existence very troubling.

And, when one ponders this issue more clearly, it become obvious that our general distaste for the medium dates back not to an inability for us to cover them... But to a few foundational debates centered a few users that simply did not like them.

When one starts to untangle our rules, what content we allow, and what content we ban, it can eventually be figured out that video games have been widely hit by a more broadly complex rule: the ban on branching narratives, AKA multipath fiction. And so, if we want to course correct on games, we also have to study the site's relationship with other narratives banned under this rule.

Multipath fiction is an extremely contentious and controversial topic, to both those who want to see these sources validated and those who don't. As we'll establish in a moment, the judgement against these stories predates our modern concept of the "four little rules", and indeed was based partially in the website seeking out a "Doctor Who canon" and trying to eliminate storytelling techniques which disagreed with the personal canon of a select few.

Over the years, many evolving justifications have been given for why these sorts of stories can't be covered. But the most consistent has been that there is no precedent, no theory of coverage, and no realistic way to go about it. And if we have no way to cover the most extreme and outrageous examples of branching fiction, then we can't cover any of it - or so the argument goes.

Today, we're going to have a few goals. First, I'll try to discuss the early history of validation and multi-path stories. Then, I'd like to present and analyze a few examples of this "genre" - listed from least complex to most complex. And then our goal for the time we have allotted is to answer four general questions:

- Where is the line? When, during this list, does covering these stories become functionally impossible for the website?

- Depending on where that line lies, is keeping all of these stories invalid justified?

- Can we come up with a theory of coverage which allows us to cover some or all of these stories?

- Is our entire definition of "multipath narratives" actually incorrect? Is there a more nuanced way to look at all of the fiction which we have given this designation?

Before we move on I want to say a few things. Firstly, I am sorry about the length of this post, but I've seen many complaints that we "Change rules on this website too flippantly", and I felt that because this rule has been around for a decade, to properly challenge it would take a lot of investment and analysis. Because of the length of the post itself, I would also encourage the admins to extend the allotted time period for this discussion, since I can imagine 30 days might barely be enough time to read this OP let alone argue against it if you aren't in favor. As a minimum, I would recommend 60 days.

But, again, I feel strongly that we can't just say "I don't like this, let's throw it out." We need to fully understand these stories and the proposed game plan if we realistically want this to happen. And if you don't, please argue against this post in the discussion area! But I do hope everyone will hear out my thoughts about why this is a conversation worth revisiting.

If you're sitting comfortably, we'll begin.

Addressing history and precedent[[edit source]]

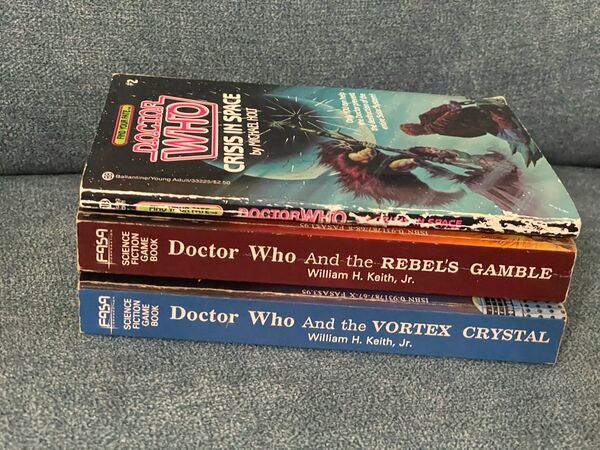

If you want to understand why multipath stories are invalid, it should be known that the topic dates back to four primary topics: Attack of the Graske, the Find Your Fate novels, The Adventure Games, and the FASA Doctor Who Role Playing Game.

On the 30th of August 2005, the TARDIS Canon Policy originally launched, written by User:Freethinker1of1. This page sought to imitate Memory Alpha's canon policy, and mostly sorted potential "sources" into if TARDIS Wiki would consider them canon. Things were very much in flux at this time, for instance the Peter Cushing Dalek films are listed as valid sources, while the novelisations are not. However, something that was set in stone from day one was that the FASA Roleplaying books were not considered valid.

The original intention of this "canon policy" was that further debates could be had to change the rules if the users deemed fit. For instance, in 2008, the Cushing films were changed from "Canon" to "Non-Canon." However, the FASA Roleplaying games being invalid was not challenged at the time. An extremely important note is that the rationale given was that the roleplaying games should be non-canon because they contradict the TV show and various books. The nature of the games had absolutely nothing to do with them being non-canon, and indeed only FASA games were targeted by this.

- *Roleplaying games (FASA) [are not valid resources] as these sometimes contain histories and other information which conflicts with the television and prose stories. (Although some material from the FASA game were later incorporated into the Missing and New Adevnture stories.)

Without context, one could easily presume that more modern roleplaying books which did not contradict the series were still valid sources.

In March 2008, a forum user at Forum:Need more info on Omega asks about the plot of the Search for the Doctor novel featuring Omega, and User:Tangerineduel questions if the novel should be canon according to policy. He argues that as it's not quite a roleplaying book, but also not fully a novel. But most importantly, he argues that covering the book is controversial because there's more than one path, with no clarity on which path "counts" as happening in-universe.

In June 2010, User:CzechOut starts the post Forum:We need a policy on videogames, in anticipation of The Adventure Games. Here, Czech directly states his intention that as the wiki has precedent against the FASA roleplaying books, all games and video games should be denied coverage by default, then debated months after release.

Per our canon policy, FASA roleplaying games are flatly disallowed, and I do think there are many problems with using videogames as valid resouces. Frankly, Attack of the Graske is tricky enough, and, to my mind, only exists as canon inasmuch as it gives the tiniest sliver of information about the Graske. But I do not believe the events and storyline described in that game actually exist in the DWU. The Doctor did not stop by your house one day and invite you on a test to see whether you could be a companion. Players of these games — that is to say we — are quite clearly not a part of the DWU.

The other problem with videogames is that, depending on how they're constructed, multiple outcomes can be possible. Thus comes the ugly and thorny issue of which outcome is canonical. Going back to Graske, we can't say whether the outcome where you lose and "don't have what it takes to be a companion" is the one we should adopt as "canon", or whether it's the "happier" ending.

If you'll note at the canon policy page, the policy on games is still said to be "in flux". We need to really hammer that out before we start incorporating material from videogames into articles. My recommendation would be to hold off citing from these things until we have a clearer notion. What would be a nightmare, I think, is if people started playing these new adventure games, while furiously jotting down notes and filling up the articles on Amy Pond, the Daleks, and the Eleventh Doctor — only to find out months from now that in fact the game had a branching architecture and it didn't actually include the same information every time it was played.

However, Czech faced minor pushback from users due to the BBC having made a statement saying The Adventure Games were canon. The game Dalek Attack is also debated, as Czech believes it to be a multi-path game (due to three Doctors being optional for the gameplay portion) while others point to the novel Head Games referencing the events of the game.

The forum goes off topic from there, with Czech making a bulleted list of reasons why City of the Daleks apparently lacks internal consistency with a post-Time War Doctor Who universe, and thus he disagrees with the BBC calling it canon.

Several months later, User:Tangerineduel makes a closing post of sorts, stating:

The video games (old and new) conventionally have a single ending and have key moments of story throughout them. It is the story/plot that we use as our source rather than the individual character/player actions. In the canon policy and on the GAME page this would be noted.

So precedent was set. Video games would not all be non-canon by default, but any game with even the most slightly-branching details would be far more likely to be called non-canon.

Now, an interesting topic is that Czech himself was remained unsure when it came to Attack of the Graske for some time. In early 2011, he began work on User:CzechOut/Sandbox8. This was essentially his earliest work at attempting to personally rewrite T:CANON, something he would later accomplish by creating T:VS.

In the sandbox, he makes this statement:

- First-person videogames, like Attack of the Graske, are non-canonical to the extent that the player, you, or your actions are not a part of the DWU. However, Graske, and games like it, are canonical, in that the observed facts, which don't have anything directly to do with gameplay, are allowable. Put more simply, Graske is a valid resource for defining the species of the Graske, but you may not refer to any impact your gameplay has on the specific Graske in the game. Likewise, Graske canonically describes that Rose Tyler saw an ABBA concert in 1979, and that a Graske came to Earth one Christmas to kidnap humans — but it does not establish that you are a companion of the Tenth Doctor.

So it's clear that Czech, for some time, considered a partial validity for Attack of the Graske. In fact, the game wasn't actually marked at invalid until December 2012. This was a result of Thread:117868, wherein User:MystExplorer asked why this game wasn't marked at NON-DWU, at which point Czech indicated it must have been added and then removed. However, according to what I can tell, it's actually a situation where no one ever added the invalid template, and the admins just presumed it was already there.

In 2012, Forum:Doctor Who: Worlds in Time brings the topic of video games back into the forefront. This is one of the first debates I took part in on the website, and as I'll discuss later I think the wrong judgement was made with this one, even beyond the topic of canonicity/validation. It's during this forum that Czech presented User:CzechOut/Video game policy, a different sandbox of his pitching his ideal policy for how the wiki should go-about covering games. These are the rules which he pitched:

- Table-top, old-school, pen-and-paper role playing games are completely disallowed. They are in no way canonical, and information from them may not, under any circumstances, be used to write the in-universe portions of articles.

- You, the player, are not part of the DWU. Thus any element encountered solely by a character that the player has created is not a part of the DWU. If an established character, such as the Doctor or a companion from television, has direct contact with an element, you may reference it.

- If the character is created and named by the game developer, then his or her actions and encounters are "in-universe". Otherwise that element didn't happen to anyone in the DWU.

- The element under consideration must not be a creation of the player. Thus, if the player creates a character, that character may not receive a page on this wiki, nor may that character be referenced on this wiki.

- The element under consideration must have narrative significance, and must occur at the same point(s) in the story, regardless of who is playing the game. NPCs without narrative significance do not deserve an article here. NPCs who do not appear at the same point in the game for all players do not deserve a page here.

- In any sort of branching interactive narrative, the outcome which is considered canonical by this wiki is the one in which the player succeeds, unless the game developer has specifically programmed failure as the only option.

- Real world pages may exist on the wiki even if in-universe ones are disallowed. For instance a List of NPCs in Worlds in Time may be a perfectly valid article, whereas articles about the individual NPCs may not rise to the level of notability described above.

While this list of rules never officially passed, they spiritually served as the basis for how and why "splintering narratives" would be banned.

As we've seen by now, Czech's biggest source of disagreement is the concept of "you" being the main character in any DWU story. Two specific examples here would be Human (Attack of the Graske) and Companion (Worlds in Time), which he specifically rails against in the debate. In the actual debate, Czech hammers home that "Any game which centrally has a character you created and uses items you created is fanfic."

Make sure to remember rule 6: "the outcome which is considered canonical by this wiki is the one in which the player succeeds." Again, this rule was never written down anywhere, but it did functionally have a role under the logic of why some games were still covered in spite of minor gripes like death animations.

Towards the end of this debate, it is pointed out by User:Tybort that the Decide Your Destiny and Find Your Fate novels have never been selected out as canon or non-canon. The topic is also connected directly back to the FASA games, and how T:CANON still stated in 2012 that they were non-canon for contradicting "primary sources." Czech states:

Clearly, the current wording at T:CAN is not the real reason the FASA thing is banned. Narrative contradiction is the rule of the DWU, not the exception, so you can't throw something out just because it doesn't jive with another story. The real reason for the ban must surely be that RPGs are internally unstable narratives. They don't come out the same each time you play them. So anything which happens differently each time you play it shouldn't be considered a part of our tardis.wikia.com canon, because we don't know which outcome to go with. This would mean things like the DYD and FYF books would also be slapped with a {{notdwu}} warning. I don't see anything wrong with saying:

Only those narratives with a consistent narrative, experienced in the same way for all those that consume that narrative, may be considered a valid source for the writing of articles. [emphasis his, not mine]

In the forum, I strongly disagreed with this suggestion, as I felt it was a little bit much. But in the end, the rule was implemented, and from that point forwards, all branching stories were considered automatically invalid on the website. Forum:Decide Your Destiny and Find Your Fate are NOTDWU from here on out clarified that Decide Your Destiny and Find Your Fate were impacted by this. Czech includes an admin chat with User:Tangerineduel where the two decide to invalidate the books for being too complex.

yeah, i think this is one case where if people complain, tough

it's too much work

Now, the most recent update on this front was that in December 2020, it was apparently noted that AUDIO: Flip-Flop technically is a "branching story". Thus, based on Czech's definition from 2012, it shouldn't be something we cover.

On this wiki, calling a story in the Big Finish Main Range "invalid" would be paramount to blasphemy, so an alteration was hastily added to T:VS. This alteration clarified that when a story depicts the branching nature of its story as "timey-wimey-ness", then it should be valid. This is a very broad change to the rules, the ramifications of which has never been discussed.

Now before we go any further, I think we have to address the elephant in the room: the dated nature of these older debates, mostly due to the constant references to the TARDIS Canon Policy.

In mid-2012, while these changes were still going on, T:CANON was changed drastically. It moved from being the main space where the website clarified what was and wasn't canon, to a page all about the concept of canon not existing for Doctor Who. This is, in a basic sense, the same version of T:CANON that we have today. After this, Tardis:Valid sources was created, becoming the new home to dictating what topics we do and do not cover.

For a time, the "Non-Canon" category of stories was replaced with "Non-DWU." But this changed in November 2015 with Thread:180396. Here, it was agreed upon by most users that Non-DWU was not a satisfactory term for invalid content. Not only did it imply that all non-valid stories fail Rule 4 and Rule 4 alone, at the end of the day the term was not fundamentally different from "non-canon."

And so, as Czech put it, “Consensus to change was (lukewarmly) established.”

Now, the reason I bring this up is that I think since 2015, and especially since the REAL early days of 2005-2008, the site has changed. Not only in priorities, but in our ideology.

This wiki used to cover Ten Doctors. That was it. And we used to have very strict guidelines about what did and didn’t fit, because we were trying to figure out what was canon to the Doctor Who franchise. Is Unbound canon? No. Is Scream of the Shalka canon? No. Is Dimensions in Time canon? No.

But now, consider the following. The Timeless Child arc has introduced the idea that there are potentially hundreds of rogue, uncatalogued incarnations of the Doctor. Big Finish has began releasing audio stories using alternate scripts from early Fourth Doctor stories, which we have covered without even needing a debate. Russell T Davies and Steven Moffat have released contradictory stories depicting the regeneration of the Eighth Doctor, both covered with equal footing. And we do not debate the canonicity of these sources, because we instead are bound to a set of internal rules which we view as entirely removed from the concept of canon.

And I believe that when we go about these debates, we truly have such a different perspective about these things that it does bring merit to revisiting this topic. I think, for instance, that covering self-insert characters is a lot less controversial for those reading this post today than it was to the editors of 2012. Not to mention that today, a video game contradicting some perceived element of the "post-Time War universe" is a lot less likely to be brought up as proof of why it shouldn't "count" on the website.

Are branching narratives non-canonical? Perhaps. Maybe Czech was right on that front. However, I don't think this should effect if they are considered valid on Tardis Wiki. Thus, I think it's entirely fair for us to re-evaluate the stories that these few forums so swiftly discarded.

Why are branching stories invalid... right now?[[edit source]]

One of the things you'll find on this wiki is that topics like this have a long history, where the reasoning given when precedent was first set is not exactly the reason given now. More recent debates have preferred to contextualize invalidating branching stories through some reading of our "four little rules," rather than the concept of canon and continuity.

So based on what I have read, these are the primary reasons that an admin today would say branching stories are invalid:

- Because these stories depict a non-consistent series of events, we can not say which version certainly took place within the Doctor Who Universe.

- Diverging narrative stories are often not even real narratives, thus they fail (the old) Rule 1, Only stories count. Not only were branching narratives considered to fail the old Rule 1, some would argue Rule 1 was partially created because of the forums cited above.

- Covering these stories is not only against Rules 1 and 4, but is technically impossible. We could not cover these stories if we wanted to. Covering multipath stories on a wiki is ugly, difficult, headache inducing, and should never be attempted. (AKA: it's too much work.)

Obviously, reason #1 was essentially the explanation given when this rule was first invented.

Personally, I don't think the first one stands up ten years later. If you actually read through Rule 4, there is no language in the text about a concrete version of a source needing to be the definitive version that is "set in the Doctor's universe." It merely states that the intent needs to have been that the story was set in the Doctor Who Universe at the time of publication. Indeed, we cover several non-GAME stories which have more than one "version" which is known to exist, such as special editions and a few other examples I'll point to later.

Argument 2 is typically the rule that's been officially cited in the past six years, even if it's not the reason the rule exists historically. For instance, in the debate for LEGO Dimensions, the closing statement stated this:

- As has been discussed numerous times this decade, any game which has multiple outcomes depending on how the player chooses to play isn't an actual narrative.

Now... Try saying that sentence to someone outside of the wiki. Try walking up to someone playing a video game and say to them, "You know, any game which has multiple outcomes depending on how the player chooses to play isn't an actual narrative." They won't react with anger, they'll react with worry.

If you want some more evidence of precedent, in Thread:117868, User:Amorkuz gave this defense of the policy as a closing statement:

- The consensus reached (re)affirms the following rule as formulated by CzechOut: all sources with multiple endings, or indeed mushy middles, are invalid.

- This directly follows from Rule 1 of T:VS: "Only stories count". If there are different endings (or different middles, or different beginnings), it is not a story, it is not a narrative. Thus, it cannot be used as a valid source.

Regardless, this argument is now effectively dead in the water, as Rule 1 is no longer only stories count but instead only fiction counts. However, even if this wasn't true... Come on. We're all adults here. Branching stories are still narratives. These never actually failed rule 1.

(Before we move on, as I'll be saying at the end of this debate, this forum will not be seeking to validate LEGO Dimensions. So while I mentioned it as a historical topic, please do not get stressed thinking I'm secretly about to call that a valid source without ever bringing it up again.)

At the end of the day, in spite of what some people will tell you, argument #3 has always secretly been the primary reason that these sources were made not-valid. If you take the time to go and read through these old forums you'll see this brought up often. Not only were the "four little rules" not considered when this choice was made, this decision predates the four little rules.

In the past decade, whenever I have approached revisiting this, the overwhelming feeling has been that there is some hesitation to allowing any branching storylines, because some of the more complicated ones would be truly, truly difficult to cover. And so, to make things easier, we cover nothing and call it a day. And it's always been about that much more than it's ever been about T:VS.

So that is the primary inspiration for this post. I basically wanted to figure out... Where is the line? If we really think some branching narratives are impossible to cover on a technical level... Then is it really justified that all branching narratives should be not-valid?

Furthermore, my mission statement today is also to construct a theory of coverage. To kind of establish the basic theory of how wiki-fying branching narratives would function. This is important to do, as evidently there is no historical approach that was ever made to do this.

Multipath narratives: A theory of coverage[[edit source]]

Precedent in Valid stories[[edit source]]

Before we discuss the theory of coverage, we should first talk about the history and precedent that valid sources can deliver to us.

As we've established, in 2010 the release of The Adventure Games created a sort-of War on Video Games, where the games were so controversial with some on the website that an attempt was made to invalidate them.

So what was really the issue? Well, in the games, you can lose. You can actually die, or worse, cease to exist. The feeling among some was that this meant that these games had multiple endings, and thus no one narrative... Or at the very least, no such thing as a unified gaming experience. If Amy and the Doctor could die, in game, how was this set inside the Doctor Who universe?

Since then, the Adventure Games have been covered as valid stories with little controversy. So how do we reconcile a story that has, as it's been said, multiple endings?

Well, there's a general acceptance that sometimes in video games, there are features which are part of the gameplay that don't necessarily contribute to the story itself. Death cutscenes are a feature of most video games, and yet there are still many sites dedicated to covering the story of video games.

Another example of this can be found in the infamous GAME: The Mazes of Time. In this title, if the Doctor is killed he regenerates and then the game resets. However, when you’re playing as Amy Pond, this same thing happens.

Despite this, we don’t typically say “Amy had the power to regenerate (GAME: The Maze of Time)” nor do we treat The Adventure Games or The Mazes of Time as branching storylines. If it doesn’t happen to Amy, it doesn’t happen to the Doctor either, it’s just a feature of the game.

The lesson here is that SOMETIMES, gameplay features are included which shouldn’t necessarily be treated as part of the coverage.

This leads us to the recently validated, GAME: Legacy. This game features a set, pre-scripted series of storylines and cutscenes that one has to earn through typical phone-game-shenanigans. You have the ability to customize your "team" to beat the puzzles and such, but this does not effect the story.

For instance, an in-game narrative might feature the First Doctor, Sarah Jane Smith, and Martha Jones. Then, during the gameplay segments, you might possibly change this team to other characters you've unlocked... But this doesn't effect the plot of the game, nor the cutscenes. The story is not effected by whatever gameplay choices you make.

Again, the lesson here is that branching gameplay mechanics do not insinuate branching storylines in-game.

The same can be said for GAME: Dalek Attack, which despite the controversy in 2010 we currently cover as a valid story. Because the cutscenes clearly depict the Seventh Doctor, we essentially deem that this is the plot to the game, in spite of other Doctors also being optional choices.

The final precedent I want to discuss comes from non-video game sources.

In 1976, as their license for Doctor Who was about to slip away, TV Comic began reprinting old Doctor Who stories, but with the Fourth Doctor's likeness (barely) drawn over them. An example of this can be found on the page COMIC: Doomcloud.

As I'll mention below, we have staked quite a long-running precedent on covering both versions of these comics. Thus, we have made a precedent of how to cover a piece of media when it has more than one "potential telling." I'll mention this again in just a moment.

Attack of the Graske[[edit source]]

Attack of the Graske is a video game designed for living rooms, where the player makes their way through the story by selecting different options. It's something like a pop-quiz, where you need to pay attention to get all the answers right. This is also the story which introduced the Graske, who became a staple of Doctor Who spin-off media in the Russel T Davies era before the species finally made a triumphant cameo in TV: The End of Time.

This is an excellent game to begin our study of branching stories, because it is perhaps the most simple "branching story" in the entire DW franchise. In total, there are really only two endings:

- Ending 1 (the good ending): The human reverses the settings, destroying the Changelings and sending all the original people back to their homes. The little girl celebrates Christmas with her family. The Doctor tells the human he did a good job, and he might come back for them one day.

- Ending 2 (the bad ending): The human freezes the base, trapping the Graske but also the kidnapped victims. Back on Earth, we see the Changelings still on Earth, laughing maniacally. The little girl's Christmas is ruined. The Doctor tells the human they aren't ready to be a companion, but they may be one day.

Besides from what's above, you can obviously get the proceeding questions right or wrong. If you get the quiz right, the Doctor says you're awesome. If you get them wrong, the Doctor tells you the right answer.

But since no realistic page would ever cover something like that, the only choice that effects the wider narrative is if the player picks the good ending or the bad ending.

The brilliant thing about this topic is that we could easily cover this story simply by using your greatest linguistic tool on this website. The magical power of the phrase... "According to one source..."

Or perhaps, more suited in this case, "According to one telling..."

So:

- According to one telling, the human chose to freeze the base, trapping the Graske but also those kidnapped. All of the Changelings remained in place, and the Doctor told the human they weren't ready to be his companion.

- But, according to a different possibility, the human instead chose to reverse the Graske's controls, destroying the Changelings and returning their victims to their home worlds. In this source, the Doctor told the human he might come back for them one day for more adventures.

To call back to what I said earlier, there ARE stories we cover on this website that currently have more than one "telling," as it were. To quote our page for 10 Downing Street:

- In 1974, the Third Doctor, Sarah Jane Smith and Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart met with the Prime Minister at 10 Downing Street to discuss the approaching poison cloud caused by the Zircon. According to another account, it was the Fourth Doctor, Joan Brown and General Maxwell-Lennon. (COMIC: Doomcloud)

Indeed, covering the two main "paths" of this story would be no more difficult than covering Revenge of the Cybermen and Return of the Cybermen concurrently, which we currently do without controversy.

The only minor hiccup I have with Attack of the Graske is that I prefer to be able to actually cite what variation I'm pulling information from when there's branching paths like this. So, if this were a novel, I'd want to cite something like (GAME: Attack of the Graske: Page 20). Here, however, I'm not sure that (GAME: Attack of the Graske: Good ending) or (GAME: Attack of the Graske: Ending 1) are nearly as objective as terminology. But if this is the only issue stopping us, I think some community consensus could find a solution.

Before we move on, I should also say that another reason this story was constantly discounted was due to "You" being the main character. At one point in this wiki's history, breaking the fourth wall or involving the audience in any way was seen as extremely controversial. However, a recent debate clarified that the website does not consider "you as the protagonist" as a form of fourth wall breaking which is disqualifying. To clarify again, we would write these articles more as "an unidentified human" and less as "you, person reading this article."

Also, if anyone wants to question the "rule-4-ness" of this source, when the Graske make their first "valid" appearance in TV: Whatever Happened to Sarah Jane?, Sarah Jane Smith comments:

That alien, he's called a Graske. There was some Graske activity on Earth a couple of years back, but no, this isn't their style at all.

I'm sure that in-universe, there's now several examples of "Graske activity" this could be referencing, but in the context of intent this is clearly a televised reference to the game. I'm not even making a case of "rule 4 by proxy" here, it's just a fact that the Doctor Who creative team in the RTD1 era thought Attack of the Graske "counted" in-universe. Historically, the game was green-lit at the exact same point as the Tardisode series, and was basically an interactive promotional episode. REF: Companions and Allies even includes "You" in a catalogue of the Tenth Doctor's companions. I don't think there's a case to be made for Graske failing Rule 4 in the slightest.

Doctor Who: Infinity[[edit source]]

So it might seem that I'm front-loading this post with video games and saving all of the PROSE branching narratives for later. This is not by design, but simply a consequence of the fact that Doctor Who video games have historically been very... Simple. Rarely doing anything outrageous or impossible to wiki-fy. Instead, what I would call very simple mechanics have often been read as "branching details" by people who don't quite understand the medium. Infinity is just one example of this.

So what's the best way to understand what Doctor Who: Infinity is? Well, you know the Real Time/Shada webcasts? Imagine you're watching one of those, and occasionally the screen pauses and you have to play Candy Crush to keep watching. That's the gist of it.

Infinity, I feel, is important to throw in here because it is not really an example of a branching piece of fiction by any real definition. But it is an example of a story which has been called one on Tardis Wiki simply for just... being a video game. And not a complex one, or a good one. It's a game so simple that it's borderline a visual novel.

The story, again, is a pre-scripted series of stories with basic animation which you can not fundamentally change or challenge no matter what you do. As far as I can tell, the only thing that varies is how good you are at Candy Crush. If you match three blue orbs, you get a power-up. That's the only thing that changes. This is quite frustrating, because I can't imagine a context where the candy crush segments could be wikified, again because it is a part of the gameplay and not the content of the fiction.

I really expected to have more to say here. This one's just sort of sad, and should be valid regardless.

The Saviour of Time[[edit source]]

So again, we're going non-chronologically here, basically sorting a few examples from least complex to most complex.

So The Saviour of Time is a 2017 Twelfth Doctor game which was playable through Skype. While it no longer works, I'm willing to bet many people here have enough chat records of this title to make this a non-issue, and our current page on it is pretty meticulous as-is.

The game surrounded the Twelfth Doctor searching for the elusive Key to Time, and recruiting a human (you) to help him in his journey.

This game, from what I've seen, does not have multiple endings. But it does feature two major elements that will be essential to discussing if we want to find a way to cover these types of stories. But both elements are actually part of the same thing: player intractability.

When entering the TARDIS, the player is asked his or her name, and the Doctor will blindly accept whatever you type after this. Type "Why do you want to know?" and he'll call you that for the rest of the game, which works as it matches the Twelfth Doctor's personality.

Next, there's the ability to get the Doctor to say unique things based on what you type into chat, be that as a response or a non-sequitur. If you tell the game that your name is Jack Harkness, the Doctor will say he once knew someone with that name. If you ask about the Cybermen, the Doctor will say: "I may never look at Cybermen the same way after poor PE became one. Actually, I rather hope I never have to look at one at all." This is a reference to Danny Pink.

So the first big question is how do we cover a character who literally has an infinite number of possible names? The answer is to just name the page Human (The Saviour of Time), and have it stated in the opening passage:

- The human's true name varied widely depending on possible tellings.

Well then, what about all these minor references which only happen if you know which keywords to type in? Here, we could make use of our old allies: according to..., if, and possibly.

So, Danny Pink's page could list under the legacy subsection:

- According to a telling of one source, a human might have asked the Twelfth Doctor who the Cybermen were. The Doctor potentially responded that he hadn't been able to look at the race the same since "PE" had been turned into one.

Already, this is acceptable language to cover the most basic user interaction without violating any of our other rules. We only discuss these branches as possible paths in a specific telling of this source.

Additionally, I should note that minor plot moments in this game do have a few forks, but not in major ways. For instance, if the user fails to control some part of the TARDIS enough times, the Doctor will take back over. But this is not so complex that it's impossible to cover. Again:

- According to one telling of this source, the human pulled the TARDIS' lever. In other tellings, it was the Doctor who pulled it after the human failed to.

Why you would want to cover a detail so specific, I have no idea. But I'm just trying to prove it is possible, as historically we have invalidated stories for branching options this ridiculously minor.

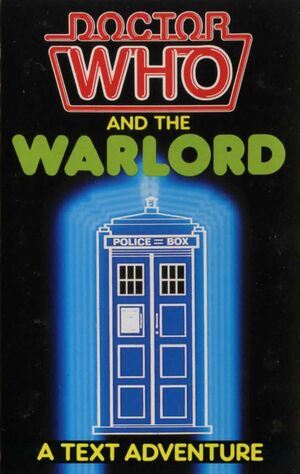

Doctor Who and the Warlord[[edit source]]

Doctor Who and the Warlord was a video game released in 1985 on the UK-exclusive BBC Micro. The game was written by Graham Williams and is a "text adventure game" where you are dropped in a world and expected to explore on your own. The opening text explains that you are traveling with the Doctor, but someone knocks you out and kidnaps him. You are thus left to your own devices and have you have to free the Doctor.

In Part B, set after you free the Doctor, you discover that the meddling Time Lord The Warlord is going about trying to meddle in wars across space and time. Here, the Warlord is attempting to change history at the Battle of Waterloo. It's up to you and the Doctor to stop him!

It took me quite a while to figure this one out. One particularly frustrating thing about these old titles is that you have to know exactly what phrases to type in for the program to accept your writing. It's basically a game about you wandering around and doing random things, and if you do the wrong kind of wandering or do the most slightly wrong thing, you are killed unceremoniously. But if you are able to figure out the specific right set of things to do, you get to the end and win. This includes typing in such meticulous chains as:

- North, North, North, South, South, Wait, South, South, Drop all, North, North, South, South, Pick up all...

And having it just be accepted that if you type in "south" too many times you die instantly.

This guide from the gamespot forums is a pretty enlightening description of how the title works. The guide lists two full paragraphs of commands separated by commas and repetitions. According to what I've been able to figure out, in order to get a 100% victory on the game you have to type in these specific text commands into chat (or some variation, for instance North can just be "n"). If you stray too far from these specific phrases, you are likely to either die instantly or fail later due to missing some minor item received by doing something mundane. I have not found any luck in straying from this set path, and indeed this guide states that even inputting a typo can lead to instant death.

As an extremely comedic example: I noticed after parsing through this info that "make bed" is in the list of required prompts. This led to a kind of mental joke that "if you don't make your bed, you die!" But guess what, I played the game! If you don't make your bed, you die.

BECAUSE when you make your bed you find a toothpick. And at the end of the game, the Doctor is defusing a bomb. He specifically says he needs a toothpick to do so. If you didn't make your bed, you blow up, and so does the Duke of Wellington!

Death is arguably quite kind of an option with this game, as there are also large parts of the map where absolutely nothing is happening, where the point is basically that it's easy to get lost with no clear way of getting out.

The speedrun of the game available at Speedrun.com is also very enlightening.

Basically, Doctor Who and the Warlord is only an example of a game with "multiple endings" if you consider getting blown up or shot in the face an "ending." As we'll talk about later in the "Find Your Fate" analysis, this is a more complex topic than one might initially believe. For instance, let's say that there is some lore which can only be revealed to the player if they face a specific death animation?

I'll give you an example. I recently created Kilroy (Doctor Who and the Warlord). I have no idea what the deal with this character is, but I suspect that it might have been a trial-and-error process where you could figure it out if strayed from the "correct path" in a specific way. I really wish there way a way to just read all the potential text in the game, but I haven't been able to figure it out myself. So what do we do about these random bits of lore in this case?

I'd say, just for this one example, we should encourage the full, 100% route to be the version of the story that we say "happened for real." And if there's something more obscure like a character's name or motivation which is explored in a death ending, then that's the only situation where we should bring info from these alternate paths up. Citing tertiary lore like that should just be an accepted part of the medium, even poorly planned examples of the medium.

Worlds in Time[[edit source]]

So, Worlds in Time is something that personally hits home for me. It's a game I played a lot when I was a kid, and I took a lot of time to try and add details about it to this site. However, after a debate, it was decided that not only would the game be considered invalid on this website, we would also effectively ban users from adding information about the game to our own page about it. At the time, there was an official BBC Wiki site for WiT, so our judgement was that we should link to that and otherwise keep it all off of TARDIS Index File.

This is one of the only times in this site's history that we've decided to give an entire licensed title to another wiki, and additionally a non-Fandom-wiki, one which was not in-universe... And that wiki no longer exists. Wayback archives of the website are also frustratingly incomplete, meaning information once stored there which is gone for good. Most of what does remains pertains to mechanics but not content.

The game has been offline since 2014, meaning there's a ton of information about it that will likely never be archived, which otherwise would have been organically on this website. So I hope I'm not over-stepping my boundaries when I say that the treatment of World's in Time is the biggest mistake ever made by Tardis Wiki.

So the point is that this is one where I'm biased, and parts of this game are lost media. But I do believe, as I did then, that covering this title was always within our reach.

Worlds in Time was an online "free to play" MMOG published in 2012. The game would start with a character customization screen, allowing you change your name, gender (male or female only) and race (human, Silurian, Catkind, or Tree of Cheem). This is absolutely a lot more complex than just changing your name. At the time, I created a page called "Companion (Worlds in Time)" to cover this character, which covered the branching details about the character in the behind-the-scenes section mostly.

Of course, the game was an MMOG, so each level is designed with four people being intended to play at once. You could get other players in the game to join your team, but if you didn't have friends who were into Doctor Who, the game had 11 NPC assistants, and would randomly assign three of them to your team. This is a minor escalation of variables, as you could play any specific level with any three of these NPCs, or none of them.

My stance in this case is that we would cover each of these characters as people who existed and knew the Doctor, but we would use language like "possibly" and "according to..." to describe their further adventures. For instance, our page on the assistant Will currently states:

- Will was an "assistant" of the Eleventh Doctor, recruited by him to try and fix time after a temporal event had disrupted the universe.

- According to one possibility, this companion may have helped another companion hunt for time shards along other assistants. Other possible assistants in these adventures included Darren, Mal, Meera, Noma, Nneka, Silas, Steven, Talia, Camile, and Gethin. (NOTVALID: Worlds in Time)

So the basic gist of Worlds in Time is there were a bunch of planets and eras in the game you could jump between, and each location had a set number of storylines to discover, bad guys to fight, allies to meet, etc. The planets included Earth, New Earth, Mars, Alfava Metraxis, Ember, Messaline, Skaro and the Starship UK.

Each planet had a series of Interventions/Adventures, which were akin to serials. Each "serial" had several episodes or levels. So if you beat around four or five levels, you had a completed serial of the game. You could also type your own "dialogue" into the game's chat window, but this didn't effect the pre-scripted dialogue going on around you, and was really just a way for people in a server to talk to each other (indeed, the chat window and the dialogue window were separate tabs). Each "episode" played out the same way every time, with the only differences I can find online between play throughs having to do with patches and some people playing the original BETA release.

But the original debate from a decade ago decided that the game was a multipath story. Why was that? Well, you could play the various episodes and planets in any order you wanted to. I remember finishing all the Earth levels first, then moving on to Ember and Messaline. But, it was entirely possible to play a few Earth levels then switch to Mars for a level, then switch to Ember and so-on. So it was decided that because the game had no single "track", and it allowed you to customize your character, it was akin to the Find Your Fate novels.

I have always thought this made no sense what-so-ever, and was furthermore an ongoing example of this website's refusal to understand fundamental video game mechanics.

If you all don't mind some non-Doctor Who terminology, as a kid I immediately compared this game to Kingdom Hearts I and II. In these two games, you go to various worlds populated by Square Enix and Disney characters, but often the order you do these levels is extremely optional. Often, you can just leave a planet without finishing the story and go start a different planet. Occasionally, a planet from the second act can be saved until literally right before the final boss. But I don't think this really impacts the story that is told in the game, and if Kingdom Hearts had Doctor Who characters instead of Disney ones, I think we would be able to cover it very effectively. Most importantly, if you told a Kingdom Hearts fan that the game series "doesn't have a real linear plot" they'd laugh in your face.

So in the case of Worlds in Time, it would be enough to just say: "This companion went to Earth, New Earth, Mars, Alfava Metraxis, Ember, Messaline, Skaro and the Starship UK." We don't even need to say "what order these events took place in varied," because it's so inconsequential to the story and arguably a huge part of how our site operates in the first place. We don't consider The Two Doctors invalid for its dubious and constantly contradicted placement in the Second Doctor's story, so why should it matter what order the WiT levels take place in?

So a game taking place in a customizable level ordering shouldn't impact our ability to cover it as a story.

At the end of the day, putting aside level ordering and the NPC assistants, there's only two details that are complex here: the fact that the protagonist has four potential species and two genders. I feel, given the language and tactics we've already introduced in this thread, covering these paths in-universe would be barely more complex than the likes of Attack of the Graske.

If we accept all of what is said above as true, the only thing making covering this game difficult is the whole "lost media" angle. Out of the 33 "levels" in this game, I'd say about 9 or 10 you can find recordings of, which is a pretty major loss when it comes to archiving Who media. But I don't think something being currently lost has ever been used to rule against something on this wiki, and I feel with some confidence that more material from this title is likely to be found in the next few years.

VR Games: The Runaway, The Edge of Time[[edit source]]

File:SPUDS Attack! The Runaway Doctor Who So from, I believe, 2020 to very early 2023... Tardis Wiki did not have a forum system. This meant that there were many stories which desperately needed validity debates in their fleeting moment of relevancy but got absolutely nothing. And the topic of this subsection covers... Well, in my opinion the least justified. VR games, which has been nearly universally invalidated... Despite at least one of these seeming to pass our rules as they currently exist.

The official policy of this website for many years is that all of the topics in this forum are non-valid for being branching narratives. But it's obvious to me that this isn't true, as some of these titles are not branching narratives. They are simply narratives with some level of interaction. For instance, the Micro:bit games did not feature good endings nor bad endings or any splintering parts. But they dared to let you be the main character, thus they were quickly presumed to be branching stories and then thrown away. So indeed we've banned elements we associate with titles like Attack of the Graske, not simply this one element. We've banned a vibe.

VR games are the latest and most infamous example of this, as merely the idea of a game where you are the main character and you control the point-of-view of the game directly goes against the rules which Czech pitched (but did not pass) all those years ago.

So let's start with the one I feel the most confident about.

Two "versions" of this game have been released, one in May 2019 and one in early 2020. Let's talk about the original first.

The Runaway was released on 16 May 2019. Alongside the game, Jo Pearce, creative director for the BBC's digital drama team, released this statement about the direction:

- Fans will find themselves at the centre of this wonderfully animated story, helped by the natural charm and humour of Jodie Whittaker, in an adventure that really captures the magic of Doctor Who. Viewers truly are in for a treat - for those who ever dreamed of helping to pilot the TARDIS, this is your opportunity!

The game's page was quickly marked as invalid, causing then regular user User:Scrooge MacDuck to leave this comment on the talk page:

- So I've got some idea, but for the record, we're calling this invalid because…? There doesn't seem to be much of a branching story, unless you want to count the order in which one picks up the toys meant to quiet down Volta. It may be VR, but storywise, it's less interactive than Attack of the Graske was.

- If the Invalid tag wasn't simply slapped on before much info surface as a reasonable assumption for a VR game, I suppose one might justify it with the fact that the new companion of the Thirteenth Doctor is offscreen and seen in first-person, implying the companion is the player, implying a fourth-wall break. Was this the idea?

- Mind you, in my opinion, that's a lot of implication and not a lot of actual problem. Given that, again, the player doesn't really get to decide the companion's actions (being merely asked to perform them by the Doctor), there would be no trouble in creating a Companion (The Runaway) page that would simply lack a picture, but otherwise be little different from any page about a minor character. The fact that the unseen companion apparently entered the TARDIS following a spaceship crash seems to point away from the fourth-wall-break of the player literally being the companion, too.

- If it does turn out that this was the reasoning we may have to hold a proper inclusion debate, but for now, just a query. --Scrooge MacDuck ☎ 20:11, May 21, 2019 (UTC)

After several days of searching, User:Shambala108 found the precedent she felt invalidated the title. Worlds in Time, the case we discussed earlier. She did not elaborate on the contents which were relevant but insisted that no new debate was needed because of the existing precedent. I might be off with my presumption here, but this is the argument I assume was meant to be made by linking this story:

I believe that Shambala108 was arguing that simply the ability to do some part of the level in a unique order was reason enough to call the game non-valid. The precedent in this case being that Worlds in Time was invalidated mostly on the logic that being able to play the level in a unique order makes something a branching narrative.

It was seeing this discussion that finally made me realize something extremely important to context. The admins of the past have pretty much been arguing that a video game can only be valid if covering one let's play is the same as every single other let's play. Policy makers have imagined a screen recording of a video game being covered, not the game itself, and thus they have effectively barred any game which has any alteration between play throughs.

This evolution in policy was confirmed in Thread:181884, when Shambala108 stated:

"The idea that cutscenes and gameplay are separate is a fundamental point of video games."

Not on this wiki. That was established at Thread:176459.

This quote again stands at total odds with the historical and foundational judgements about video games. In short, while the original judgement was that branching storyline elements makes a game non-valid, by this point the claim becomes that even branching gameplay elements is enough to do the same, because the site officially does not seem to mark a distinction anymore.

- (If you're wondering, Thread:176459 was LEGO Dimensions, which this forum will not be validating. But the debate is historically important because the ruling was that LD was not a narrative because it s features optional side missions and easter eggs.)

But the most telling quote I found while researching this comes from CzechOut in Thread:236104, an early discussion about GAME: Legacy:

I agree that we should allow the narratives, as long as they remain non-branching, static narratives that are the same for every player, every time they play the game, regardless of how they play the game.

But I think it's important to stress that we're in the very early stages of this game's life-cycle. We don't know what's going to happen with it. Aspects of it could change. As they improve the platform, it could well be that future stories will indeed have branching narratives, and then we'll be in the very sticky situation of being okay with some of the stories and not okay with other ones...

If they do upgrade the current static versions into branching narratives, would the result not be that there was once a valid narrative, it's been "lost", and where it once stood there is a non-valid video game "adaptation" of the original?

To improve your game is to make it automatically non-valid on Tardis Wiki. That is our official policy.

This represents a problem - the "no branching narratives" rule is the definition of a slippery slope with no boundaries. If an easter egg makes something a branching narrative, if a dialogue option makes something a branching narrative, if the ability to solve a puzzle by picking up items in a unique order makes something a branching narrative, if the ability to pick and choose levels in no concrete and consistent path makes something a branching narrative... Then yes, this rule will consistently be used to invalidate anything short of a let's play.

Anyways, back on The Runaway's talk page; several other users voiced their opinions that the game should be valid and justified debate, but Shambala108 reiterated their stance that the Worlds in Time comparison made the topic null. And so, one year later, someone tried to find a loophole.

On the one-year anniversary of the game coming out, the Doctor Who YouTube channel released a "webcast" version of this game. What this meant was this was, essentially, an official let's play uploaded to YouTube - making it nearly exactly what our rules are asking for.

And so, User:RingoRoadagain created The Runaway (webcast). On the talk page, he made his intentions very clear:

- I don't think we should merge this article with the video game. One is interactive while the other is not. I assume the interactivity was the reason the VR game was deemed invalid so that could even change the validity of this story if we merge RingoRoadagain ☎ 21:31, February 8, 2020 (UTC)

However, after several revisions, User:Scrooge MacDuck added Template:Invalid to this page as well, saying that they would have to debate the title when the forums were back. I presume, at the time, he did not know that a version of the forums would not return for another 27 months. This was one of the first actions Scrooge made as an admin, as he had been granted the position a mere 48 hours earlier.

Let's jump back to 13 November 2019, when a new VR title hit our shores: The Edge of Time. Like before, the game was considered non-valid upon release, and our old friend User:RingoRoadagain decided to speak up about it.

- Hi, I am not familiar with the policy arround it but do we need a debate to put this story as valid. It's just as linear as the Adventure Games with the Eleventh Doctor (maybe even more) so it seems a no-brainer to me.RingoRoadagain ☎ 15:24, November 16, 2019 (UTC)

- No debate is needed because we've already had the debate about this kind of game/story. I'll look up the relevant discussion(s) later and get back to you. Shambala108 ☎ 17:32, November 16, 2019 (UTC)

As Shambala108 leaves to find evidence, Ringo and Scrooge discuss matters further. Scrooge states that be believes that, historically, games where you are "the hero" automatically are non-valid. Shambala108 soon returns with very little victory in terms of finding historical quotes relevant to the discussion.

- Ok, here's the first example I found, but I know there's better reasoning elsewhere, which I am still trying to find: Talk:The Saviour of Time (video game). More to come... Shambala108 ☎ 01:00, November 17, 2019 (UTC)

However, more was not to come, and Shambala108 never found more evidence.

In the following years, more users chime in that you being the main character is not a good enough reason for non-validity, but the talk page naturally goes nowhere. This game was later expanded and re-released as The Edge of Reality, causing me great personal confusion as I wrote this.

Besides from this, VR titles have really had very little debate and remain a point of great contention.

The Lonely Assassins[[edit source]]

If you're reading these sections out of order, this part basically bleeds directly from the previous subsection.

As our final video game of the forum, we have The Lonely Assassins, what some have called the greatest, most immersive Doctor Who video game ever made (because they haven't played LEGO Dimensions yet). The game came out on 19 March 2021 and was made non-valid by Najawin the same day, causing a brief edit war between him and User:BananaClownMan. These were the edit summaries:

- Najawin, adding Template:Invalid: (Pretty sure precedent is for topics that are likely to be invalid (such as video games) we assume invalidity until proven otherwise on the page)

- BananaClownMan, removing Template:Invalid: (Video games are not automatically invalid, though the VR games generally are. Is this VR?)

- Najawin, adding Template:Invalid: (No, but it is first person. "the player, as themselves" (Also, I didn't say "automatically invalid" I said "presumed as such until shown otherwise".))

Nine days later, a talk page discussion broke out:

- Could this not be classed as a valid source? Having player the game, I would argue that unlike Attack of the Graske, choices made by the player in this game don't change any aspect of the story. The player themselves is simply referred to as "civilian", with no real personalisation. It would appear that the main choices which can be made here are in deciding what to text to Osgood, though this is merely to gain information rather than having any effect on the storyline itself. Osgood talking to the audience member is just a case of breaking the fourth wall, as the Twelfth Doctor did in the valid Before the Flood. As a puzzle game, I feel this should be considered just as valid, if not more valid, than games like The Eternity Clock or Blood of the Cybermen for example, in which players take control of characters themselves. 66 Seconds ☎ 00:08, 28 March 2021 (UTC)

- With respect to video games, that's not quite how it works. The idea is that if the playing experience (i.e. the story) is different for different people, it can't be a valid source, similar to stage plays having potentially minor variations that make it impossible to have one straightforward story. In this specific case, you yourself stated that any player can text different things to Osgood, therefore the story will not be the same for every player. Shambala108 ☎ 00:16, 28 March 2021 (UTC)

Scrooge later entered the chat indeed indicated that branching gameplay elements were the deciding factor:

- @Epsilon: well, yes, if it was just a matter of what we type being variable, without it affecting the gameplay in any way whatsoever, I think that would be fine. But that's not what's going on here. Obviously, depending on what you text, Osgood's answers will vary also. Under current policy, if that's true, then it cannot be a valid source. Scrooge MacDuck ☎ 03:36, 28 March 2021 (UTC

Now here's what I find "interesting" (see: annoying) about this... What we're seeing here is actually the slippery slope in real-time.

That policy and precedent points towards a ban on branching dialogue options is actually a misnomer up to this point. Because if you actually go to Talk:The Saviour of Time (video game), which Shambala108 linked earlier, you'll see that then-admin Amorkuz originally stated that alternate dialogue options are only excluding features in titles where the entire game is typing out dialogue options.

- As OttselSpy25 knows from having participated in them, over the years there has really been a lot of suggestions that this or that non-linear first-person game should be valid. To quote from a recently closed thread on the same topic (though not from its closing argument), all stories with multiple endings, or indeed mushy middles, are invalid. Well, this is a case of a mushy middle. It's all good and dandy to talk about the differences being confined to the dialogue. But this game is almost exclusively dialogue, infinitely variable (and not very smartly written and executed) dialogue. Worse than that, dialogue that is sometimes skipped as a matter of bug. The page clearly states that for one of the tasks, if you do not solve it fast enough, the Doctor solves it for you. This is not an "Easter-egg" difference. This is the matter of who saved the world, so to say. Plus, are you really proposing to make valid a game where the Doctor can potentially be tricked into answering "yes" or "no" to an arbitrary question? And then we'll be editing pages based on screenshots with these yes/no answers to questions invented by Skype users? Forgive me but I fear that way leads to madness, as they say on Big Finish podcast. Amorkuz ☎ 22:47, June 5, 2017 (UTC)

So, in reality, it was directly stated that invalidating this story based on branching dialogue options was a one-off thing. This is an example of the slippery slope by design. Implied policy is here pulled from a talk page where that policy was actually disputed. Because Amorkuz said one specific game is invalid for having branching dialogue, all games with branching dialogue are non-valid.

This is the issue with this rule in general - it has no clear definition in-text, and thus every single time a story is invalidated for being a "branching story," the definition of what a "branching story" actually is expands slightly.

As the talk page surrounding The Lonely Assassins continues, EPSILON adds this:

It's much bigger than just this one story, and I think that it applies to many more stories, so perhaps it's more suited to a Forum thread.

Scrooge responds:

- Well… It would if we had a Forum, but we don't, so we're kind of stuck.

- That being said, as I've said already, the reason for The Lonely Assassins's invalidity is just the "variability" of the storytelling; the fact that you can unlock different bits of dialgue [sic] from Osgood from one playthrough to another. Not that it's told in the first-person POV. In fact I see no objection to the creation of Civilian (The Lonely Assassins) — only, as an {{invalid}} character page. Scrooge MacDuck ☎ 23:42, 28 March 2021 (UTC)

From this point forwards, the issue of "you" being the hero has no longer been discussed as an issue on the website. This talk page was also what caused Scrooge to add the most recent change to the "branching narratives" rule at T:VS, justifying that admin proclamations indeed did carry weight in the talk pages in an era where the forum didn't exist.

One thing you should know is that after these debates it was discovered that there is a secret ending to The Lonely Assassins which does not contradict the "real ending" but still would have been quickly called "branching" had it been caught by the admin team.

In general, this wiki has had a very very messy relationship with video games, where our standards essentially ask that a game... Well, not be very good or interesting in order to be covered. But I think in most of these cases it's very easy for us to imagine a flip being switched and these games being covered like almost any other story.

These next few stories... Are an exception to this.

Find Your Fate: Search for the Doctor[[edit source]]

Okay, so here's where we start to get back to stories with multiple paths and indeed multiple endings. It's interesting to note how this is supposedly the definition of this "genre" of fiction, yet so many examples so far haven't really matched that energy. Basically, a lot of what we've discussed so far could be changed to valid without fully erasing the branching narratives ban. The rest of this content... could not.

In this segment we are now going to be discussion one of the "origin" topics which kickstarted the entire kerfuffle about branching narratives waaaaay back in the day. Specifically, I am going to be analyzing the 1986 Find Your Fate novel Search for the Doctor.

Before we start this, I have two things I'd like to discuss. Firstly, you'll note that throughout this thread I've been using the American title for this series, Find Your Fate, instead of the original British title, Make Your Own Adventure with Doctor Who. This is for three primary reasons. Firstly, I am American, and thus feel I have some oath to use the American title. Secondly, Make Your Own Adventure with Doctor Who is a horrible title to have to type out a bunch of times. And thirdly, Find Your Fate has historically been the title used when addressing these books in the forums.

Next, some of you might wonder why this segment is about Search for the Doctor instead of the FYF in-general. Well, here's why.

Since this topic has been historically staked in the idea that covering these sources is not just ill-advised but impossible, I think simply discussing the existence of this series isn't enough. So, in as many cases where I have time, I actually want to go out and make infrastructure and pages in the NOTVALID subspace. This way it's not simply me saying "We should let people cover these however they want to," but rather me saying "This is how I want us to cover these, and this is the sort of page I want to be on the mainspace."

So let's talk about Search for the Doctor.

One of the first shocking things I discovered about this book, or at least the American edition which I purchased off eBay, is that there are actually two kinds of numbers marking various page. One type denotes the chapter (as any regular novel might), and the others denote the "turn to x" markers. The latter is not the page number, as this novel doesn't have "page numbers." In some cases, you'll have 19 listed at the top of several pages. In other cases, several segments are on one page (see image).

I decided to call these "Marker X" pretty much universally. While it is terminology I made up, I find saying "Marker 3," "Marker 5," "Marker 15," etc makes it very clear what I am talking about. This is only appropriate for the FYF novels, where "Turn to 3" does not refer to the actual page number itself.

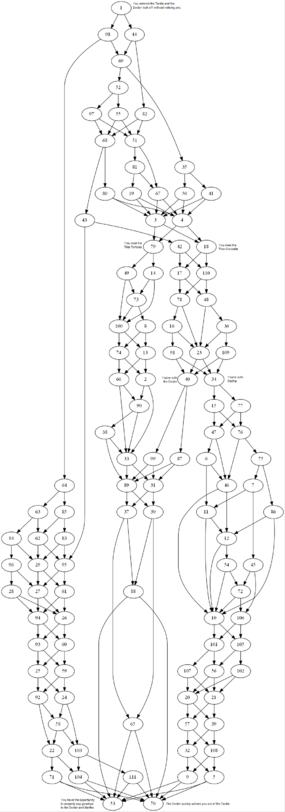

Real quick, to create this forum post I actually had a lot of help from User:Poseidome, who studied several of these novels and created a series of "graphs" showing exactly how the segments link together. This was extremely important to helping me figure out how to cover the novel, as it made it very easy to figure out the "chronological" order of events. You can see the chart to the right of this text. Not only will I be showing quite a few of these charts from here, I also believe that we should eventually have a visual like this one on the page of any branching story where it might be possible.

The first thing you need to accept when reading these books is that they are written in the second person, past-tense. Whereas the first person (I did this) and the third person (The human did this) are generally pretty common in DWU fiction, the second person (You do this) is a little irregular. Second person past-tense (You did this) is downright surreal.

But if you being the protagonist is a major turn-off for any of you, you'll be quite happy with the Find Your Fate series. Instead of writing the novel as if you are the protagonist and have wandered into the story, the novel it creates a very specific OC who is distinctly unique. You are a teenage girl named Dinah, you live in 2056, and you're descended from someone who knew Sarah Jane Smith. At the start of the story, you collect a crate, which has been in storage for 50 years, with a marker that the contents belong to Smith.

After this point, you meet Drax, who is interested in buying the crate before you've even opened it. He offers to sell it to you for upwards of €25,000. You then have the option of accepting his offer (Marker Five) or turning him down (Marker Two). If you accept his offer, two splintering endings become possible: in one, you are robbed and lose the money, and in the other, you outwit the robbers and deposit the full wealth. In both cases, you spend the rest of your live wondering what adventure you missed out on by choosing the money.

Turning down the money (Marker Two) causes Drax to eventually reveal that the crate contains none-other than K9 Mark III, who Sarah Jane put into storage for you to find in the future.

- (Yes, this does set up a pretty obvious and infamous contradiction with TV: School Reunion, at least as we cover it. In the story, K9 Mark III is blown up in 2007, and replaced by K9 Mark IV. However, there's actually a great discrepancy over if K9 Mark IV is actually K9 Mark IIIb, as he's called on some merchandise. So at the end of the day, there's about three different possible places we could put this information if this was all valid, either before SR, after SR on K9 III's page, or after SR on K9 MIV's page...)

So right off the bat, before any of the central plot has happened, we have already come across two potential endings to the novel. So the question is, in a story where there are multiple paths to multiple endings, how do we cover the story?

One theory I have is that citing stories like this could be greatly improved by {{Cite source}}, which is an experimental citation template being created by User:Bongo50. If you haven't seen it in action before, it allows you to add more information to a collapsable box. This is merely experimental, so we could not use this on pages until it is officially launched. BUT I want to show a few examples of how improving technology like this could make covering these stories easier.

One theory here is that if we could just customize our story citation, covering these stories as a set number of tellings is much easier in practice. Typing [[PROSE]]: {{cite source|Search for the Doctor (novel)|precisecite=Marker 0}} creates PROSE: Search for the Doctor [+]Loading...{"precisecite":"Marker 0","1":"Search for the Doctor (novel)"}. So in action, the analysis could someday look like this:

- Two potential tellings of this source indicated that the Dinah accepted the money. After being paid by Drax, she was either robbed by a pair of thieves (PROSE: Search for the Doctor [+]Loading...{"precisecite":"Marker 5, 8","1":"Search for the Doctor (novel)"}) or outmaneuvered the thieves, depositing the gold bars in the National Bank, living a life which was safe but filled with regret at never knowing what was in the crate. (PROSE: Search for the Doctor [+]Loading...{"precisecite":"Marker 5, 13","1":"Search for the Doctor (novel)"}) However, the plurality of tellings indicated that Dinah did not accept Drax's offer, instead asking first to see what was in the crate. Drax helped Dinah open the crate, revealing K9 Mark III inside. (PROSE: Search for the Doctor [+]Loading...{"precisecite":"Marker 2, et. al","1":"Search for the Doctor (novel)"})

You can see here that this allows us to cover the various "endings" and "paths" of the novel as co-existing sources. The hardest part about consistently using this will be finding terminology which applies to every source. In this case, the "Marker" system works pretty well for this book, but for things like video games and the like, we'd need other terms, and specifically terms that could be cited with consistency (Ending 1, Ending 2, etc).

Sadly, as this template is not currently live, I'm going to have to recommend a temporary solution whilst we wait. So it is currently my prerogative that we instead cite these markers as if they were episode titles in a larger serial. So typing [[PROSE]]: ''[[Search for the Doctor#Marker Two|Marker 2]]'' creates PROSE: Marker 2.

A heated debate back in the day was that it was ambiguous which "path" or "ending" takes place in the novel for-real. Having read through every branch, I actually disagree. The novel constantly pushes you to do back and try another path if you end up at a dead end, and very few of the "alternate endings" do not feature some extremist situation (i.e. the Doctor dies, Earth is destroyed, you're shot in the face, Gallifrey is conquered). Two quotes stand out to me:

As Omega blasted you into non-existance, you realised the mistake you had made. Although all futures are possible, only one, out of the millions that can happen, will actually take place.

Bring yourself back to life, learn from your mistakes, and go back to the end of 26 for another attempt.

Now, I ask. Does that not sound timey-wimey? Does it not sound like something out of Undertale?

It's very explicit, at least to me, that the longest chain is considered the "true path" that is solidified in-universe.

Now, we can't exactly use the "Bring yourself back to life" quote in article, in my opinion, as it's akin to a "Gameplay mechanic" which is not really part of the fiction. The game has a lot of stuff like this. For instance, you're often asked to roll two dice to decide your fate in certain situations.

But on that note, some could potentially make the case that the "bad endings" in novels like these are actually more akin to death animations in video games. Think Amy regenerates. If that's the case, does this mean that these bad endings are also simple mechanics, and thus shouldn't be covered?

Well, I don't think so. First of all, there's a lot of information we gain through the story which pertains to the lore of 2056, and if we remove these sections there's pretty important info that's missing. The side paths are also often extremely interesting and provide lore and characters you never see if you only focus on "winning."

Secondly, removing entire Markers of this novel is a pretty hefty precedent that would probably end up failing the more novels we look at, particularly potential sources where there is no singular "correct" path forwards. Even in the case of Search, one "alternate ending" in the book is actually later clarified to have happened no-matter-what, as Marker 6 is rewound to in Marker 28.

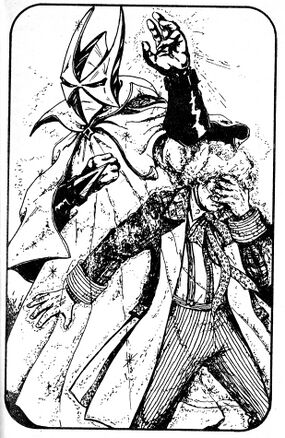

And thirdly, most of the illustrations in this book are actually from the so-called "bad endings" which are not a part of the longer, mainline path.